Skilled trappers struggle as vital insect habitats vanish.

As twilight blankets Masaka’s industrial zone, Karim Damba commences his work. He positions corrugated steel sheets, linking them to empty oil drums lined with black polythene bags and supported by lengthy wooden pieces. As 8 pm approaches, he switches on fluorescent lights, anticipating the arrival of grasshoppers.

“Since October 25, I’ve been at this,” Damba mentions, adjusting his skullcap. Damba operates as a grasshopper trapper in central Uganda. From October to December, his nights revolve around awaiting the insects to land on the metal sheets and drop into the drums. These protein-rich bugs are packaged and transported for sale in the market.

On a calm night, fortunes may favor Damba and his fellow trappers. “Sometimes they arrive at midnight, other times at 5 am,” he remarks, highlighting the unpredictability of their appearances.

Ugandans value insects, rich in fiber and omega-3 fatty acids, as a nutritious snack when fried and salted, forming a crunchy treat.

Known locally as “nsenene,” these insects emerge biannually, gracing April-May and October-December. During these periods, professional catchers set traps while children eagerly try to capture the bugs before they flutter away.

However, this year presents a contrast. November, typically hailed as “musenene,” witnesses swarms being sighted and captured almost daily, especially in central Uganda, their primary breeding ground. Yet, last month, these insects only appeared for a brief seven-day period. Their absence raised concerns at the highest echelons of the country.

“Where are they?” inquired Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni on X (previously Twitter). “Climate change? … I always wish the nsenene good luck.”

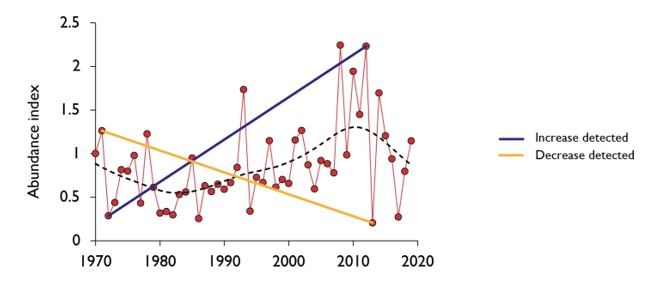

The grasshopper population has steadily declined due to the destruction of their feeding and breeding grounds in forests, grasslands, and swamps. Uganda has lost nearly a third of its forests in the past three decades, with the central region witnessing the most significant clearance of protected habitats.

This year marks the most severe decline in grasshopper populations on record.

By 6 am, Damba has only filled half a sack, expressing disappointment: “It wasn’t a productive night.” During the prime musenene days, he could fill up to 80 sacks, each fetching around 60,000 Uganda shillings (£12.50). This year, he’s far from reaching that tally.

After covering council taxes, land rent for trap setup, labor costs, and nightly electricity expenses, Damba frets over the possibility of not seeing returns on his investment this year.

Quraish Katongole, leader of the Old Masaka Basenene Association representing grasshopper trappers, voices concerns about the imminent disappearance of grasshoppers. “Whenever forests are destroyed, weather patterns shift, pushing the grasshoppers away,” he laments.

“We’ve spent money on bulbs, iron sheets, electricity, and land. Just the electricity expenses, running lights every day for two months, cost 1.7 million Uganda shillings,” Katongole explains, highlighting the financial strain and debt incurred.

Dr. Giregon Olupot, an agricultural scientist at Makerere University, warns of the looming extinction of grasshoppers due to the increasingly hostile environment. He emphasizes the critical role grasshoppers play as a protein source, especially for those unable to access alternative protein sources.

On a dreary November morning at Katwe market in Kampala, grasshopper traders await the insect delivery with anticipation. Discontent looms among them as the day’s supply comprises just three half-filled sacks.

“If this is what’s coming from upcountry, I’m disappointed,” one trader remarks, reflecting the collective dissatisfaction.

Traders negotiate prices with harvesters, eventually settling at 400,000 shillings for every half sack due to scarcities driving up trading costs. Retailers then vend the limited insects in small cups for 15,000 shillings each, a steep increase from the usual price, which would have been a fraction of this amount in times of abundance.

The decreased grasshopper count translates to reduced work for the market’s casual laborers, tasked with cleaning the insects and removing their wings and legs before sale. Jesca Nanyanzi, employed at Katwe, notes, “We earn 700 shillings per cup for cleaning grasshoppers. When the insects aren’t delivered, we’re out of work.”

Although early December witnessed a rise in grasshopper numbers and a larger supply arriving at the market this week, it offered no respite to shopper Nelson Abamanya. “I usually purchase fresh grasshoppers, but I haven’t found any. Missing out wasn’t how I intended to conclude the year.”