The stunning northern French coastline served as a muse for some of the nation’s most renowned artists. Their artworks will now be featured in exhibitions throughout the region

“Each day here brings a new sky and sea,” notes Anastasia Kharchenko, as a steady drizzle taps on our umbrellas. “Sometimes, the horizon is obscured by dense fog, but during certain months, the colors are simply breathtaking.”

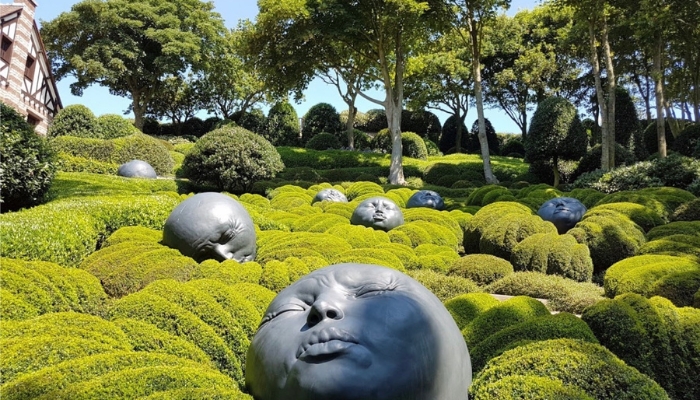

We stand atop a grassy bluff overlooking the town of Étretat on Normandy’s wind-carved Alabaster coast, with its rugged chalk cliffs jutting into the turbulent waters of the Channel. Kharchenko, head of cultural partnerships at the Jardins d’Étretat, describes the gardens’ intricate designs cascading down the hillside, adorned with whimsical neo-futurist art installations. I apologize for the dreary English weather as we gaze toward Étretat’s renowned chalk arch and needle rock formations, which protrude from the cliffs like an arm lazily stretching into the churning waves below.

Claude Monet frequented this area in the late 19th century and painted this dramatic coastline just north of Le Havre over 100 times. He was drawn to these capricious weather conditions because they added a unique atmosphere to his work. Although Monet and the other Impressionists were renowned for their ethereal portrayals of outdoor life here and in the tranquil Normandy countryside, their work was first exhibited together 150 years ago inside a Paris photography studio.

The sunlight reflecting off paintings by Renoir and Pissarro seems appropriate for a museum boasting the largest Impressionist collection outside Paris

Disenchanted with the elitist tastes of the Paris Salon, a group of artistic rebels, including Monet, Renoir, Degas, and Cézanne, organized their groundbreaking Impressionist exhibition in April 1874. This year, the Normandie Impressioniste 2024 festival, starting on March 22, is hosting various events to commemorate the 150th anniversary of this pivotal moment in art history, with exhibitions in the coastal town of Deauville, Caen, and many other locations across the region.

Among the works exhibited in 1874 was Monet’s “Impression, Sunrise,” a hazy, loosely brushed portrayal of the industrial port of Le Havre with a red morning sun reflecting on the water. Painted in 1872, it is considered the first Impressionist painting and gained notoriety largely due to the condescending remarks of critic Louis Leroy, who inadvertently coined the term “impressionism” in a review published in the magazine Le Charivari on April 25, 1874: “Impression, I was certain of it. A preliminary drawing for a wallpaper pattern is more finished than this seascape.”

Monet was raised in Le Havre, and at first glance, the modern city may not evoke the dreamy origins of impressionism that one might imagine. Upon arriving by train from Paris, I step out of Le Havre’s station into the solid and expansive Cours de la République. The tram to my hotel smoothly travels along the broad Boulevard de Strasbourg, bordered by a neatly arranged cluster of concrete apartments—a result of earlier structures being destroyed by Allied bombs targeting Nazi positions in September 1944. After World War II, architect and concrete expert Auguste Perret was tasked with rapidly and economically rebuilding Le Havre.

By the time Perret finished his work in the 1960s, the city’s stark grid of blocky streets forming the new center ville led to Le Havre being unkindly dubbed “Stalingrad-on-Sea” in some circles. However, context is key, and the more time I spend here, the more distinct and unique it feels. Nowhere else in France looks quite like this. Its straight lines and orderly layout possess a peculiar charm, reminiscent of some Japanese cities. Its modernist appearance was eventually recognized by UNESCO in 2005.

“Here, we consider Normandy the birthplace of impressionism,” explains my guide Lise Legendre, as we wander along the sea-sprayed boardwalk of Le Havre’s Saint Adresse neighborhood, where Monet resided. Fixed panels displaying 19th-century impressionist works along the boardwalk offer intriguing comparisons with the present-day landscape.

“But to become famous and sustain themselves as artists, they couldn’t stay here,” Legendre explains. “They had to go to Paris. That’s how we connect Normandy and Paris. We’re being very diplomatic about it.”

Paris was the ultimate goal, but Monet discovered himself and his style here. Hillside houses cascade down to this corner of Le Havre’s undulating pebble beach, while glass-fronted bistros, gearing up for the summer season, line the boardwalk. On the horizon, the murky silhouettes of container ships creep along slowly, awaiting entry into the port. Back in town, the Musée d’Art Moderne (MuMa) is preparing for an intriguing exhibition opening in May. It will explore the relationship between impressionism and the sepia-toned formative years of 19th-century photography, and how those images liberated artists to move away from literal depictions of the world around them.

Natural light floods in through MuMa’s grand floor-to-ceiling windows, and the sunlight dancing across works by Renoir and Pissarro feels appropriate for a museum boasting the largest impressionist collection outside Paris. In this context, light becomes a celebration.

“Impressionist paintings are a part of my childhood,” says new MuMa director Géraldine Lefebvre, who conveniently grew up on Le Havre’s rue Claude Monet. When asked why the works of Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, and others still resonate after 150 years, she explains, “Because they depict daily life. They are full of life, colors, and atmospheres. You can feel the landscape. Maybe they’re not intellectual, but they’re paintings that people can approach and understand.”

Monet’s obsession led him along the winding banks of the Seine to Rouen, a charming city adorned with pastel-colored half-timbered townhouses and known for the towering charcoal-black spire of its tri-tower cathedral – France’s tallest at 151 meters. He painted the intricate facade of the Gothic cathedral 28 times in various lighting conditions, with the ghostly series becoming one of his most revered. Starting from May 24, American artist Bob Wilson’s Cathedral of Light show will illuminate the facade every summer evening, accompanied by music from Philip Glass and words by Maya Angelou.

For now, it’s a surprisingly warm March afternoon, with tourists in T-shirts lounging on permanent wooden deck chairs outside. I stroll through Rouen’s winding medieval streets to the Musée des Beaux-Arts, where another exhibition is about to open by one of Normandy’s unexpected residents.

David Hockney has lived in the area since 2019, and his “Normandism” exhibition features vibrant green landscapes and playful iPad portraits of his friends and loved ones. Entry is free, and the exhibition runs from this month until September 22. Its juxtaposition with masterpieces by Monet and others is quite inspiring.

France’s largest impressionism exhibition, “Paris 1874 Inventing Impressionism,” opens later this month at Paris’s Musée D’Orsay, but the Seine and Normandy may leave a greater impression, regardless of the weather.