Adored by Pet Shop Boys, the paninari subculture embraced lavish fashion, fast food indulgence, and a passion for pop music, while some members flirted with far-right ideologies. Now in their middle age, its former scenesters elucidate the allure of this intriguing movement.

In a small town called Foglizzo, located in northern Italy, a group of a dozen men on motorbikes, donning vibrant attire, gathers at a snack bar on a sultry June afternoon. They are the paninari gang, an unmistakably Italian youth subculture that once dominated the scene.

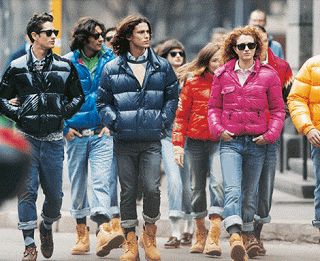

Now in their 50s, these paninari, like the ones we meet during the town’s annual courgette festival, still hold true to their distinctive style. Despite the signs of aging, they maintain their smart appearance, clad in typical paninari fashion featuring Timberland boots, cowboy-style belts, and flashy sunglasses.

During the 1980s, the paninari aesthetic flourished, characterized by a blend of designer clothing and rustic accessories, and a penchant for showcasing expensive brands. This trend defined the decade and brought them into rivalry with other youth tribes such as punks and metalheads. However, the paninari’s popularity surpassed both, as many Italians over 45 can attest. Despite producing popular books, films, and comics during the ’80s, the movement swiftly declined, finding itself on the outskirts of the mainstream by the early 1990s.

Nonetheless, a devoted group of paninari remained unwavering in their beliefs, keeping the subculture alive through the decades. Recently, their passion has experienced a resurgence, finding newfound popularity online.

Paninari, known for their rebellious spirit, defied traditional Italian culinary norms by indulging in hamburgers. Among the iconic places of this subculture, the Burghy fast-food outlet in Milan held a special place. While Italy boasted a rich bel canto tradition, these rule-breakers deviated to embrace Anglo-American pop singers like Duran Duran. The band’s song “Wild Boys,” occasionally Italianised as “uah-boee,” became their unofficial anthem. Other beloved artists included Culture Club, Cindy Lauper, Wham!, Madonna, and Michael Jackson. Additionally, the Italo disco genre, crafted by Italian musicians like Gazebo and Den Harrow, fused melodic Italian pop with synthesizers, with some artists pretending to be Americans and singing in English while hailing from places like Milano.

Within the paninari universe, Verdoia emerges as a minor celebrity, managing an online community and directing two films dedicated to paninari. Each year, he organizes gatherings attended by prominent figures from the ’80s, along with numerous informal meetings like the one in Foglizzo.

According to writer Paolo Morando, who authored the book ’80: The Beginning of Barbarism, the paninari subculture is emblematic of a significant social shift. While the 1970s in Italy were marked by political tensions, the 1980s saw a decline in political engagement and a return to a more private life. The country experienced remarkable economic growth, granting access to goods that were previously considered luxuries. Paolo Morando explains, “People began acquiring second cars, holiday homes, and there was a substantial increase in the consumption of exotic fruits.”

Within this context, the paninari emerged as a representation of the zeitgeist, a subculture associated with winners and cool individuals who were perceived as successful and affluent. Originating in Milan’s affluent city center, particularly around the snack bar Il Panino, the paninari scene initially catered to the wealthy. However, as time passed, middle-class youngsters also joined the ranks, even if it stretched their budgets.

Embodying a distinctive look, the paninari’s fashion could be quite expensive, costing up to a million lire, a significant sum for youngsters who often had to rely on their parents for financial support. Giampiero Trolio, a 54-year-old paninaro and a computer engineer in his professional life, reveals that the outfit typically comprised abundant hair gel, flashy sunglasses, high-waisted jeans, and diamond-patterned socks – the latter being a true signature of the paninaro. As they stand together, a small crowd of onlookers gazes at them, along with the collection of bikes and scooters – all models from the 1980s, such as Yamaha, Ducati, and Garelli – parked outside.

The paninari subculture is often associated with right-wing ideologies, and while there is some truth to this, it is a more intricate situation, as Verdoia explains. In its early stages, many paninari were connected to the San Babilini, a group of young fascists who gathered near Milan’s Il Panino bar in Piazza San Babila. However, as the movement expanded, it gradually shed its political affiliations and became increasingly apolitical. Verdoia emphasizes that while some members were right-wingers and even associated with the Youth Front, the youth wing of the now-defunct neo-fascist party Social Movement, most paninari were not interested in politics at all. Their primary focus was to savor life and indulge in its pleasures, leading some to label them as shallow.

Around 1983, the paninari transformed into a mass phenomenon, representing the epitome of Italian youth culture. They faced ridicule, including a popular skit on national television, but also enjoyed their own magazines and even a literary genre. One notable example was the novel “I Will Marry Simon Le Bon” by teenager Clizia Gurrado, which became a bestseller and was adapted into a movie, although the marriage with the Duran Duran frontman never materialized.

The British band Pet Shop Boys took an interest in the paninari during their visit to Milan to promote their debut album “Please.” They subsequently released the song “Paninaro” as the B-side of their single “Suburbia,” with lyrics that encapsulated the paninari’s philosophy of pleasure, cars, and fashion: “What I do like, I love passionately.” Although the band was not particularly beloved by the paninari, they admired their fashion sense.

As the 1990s brought stagnation to Italy, the paninari’s hedonistic lifestyle fell out of favor, but some enthusiasts, like Enrico from the small town of Pinerolo in north-western Italy, continued to embrace their iconic music and fashion, ensuring that the paninari aesthetic will persist.

Ironically, despite being a subculture that embraced foreign influences, the paninari now feel nostalgic for a time when the world was smaller and before globalization took hold. Verdoia explains that the mind of a paninaro yearns for a bygone Italy, a time surrounded by traditional customs, and where “made in Italy” clothes were genuinely produced in Italy. In contrast, with the advent of globalization, manufacturing has been outsourced and decentralized.

Interrupting, Troilo, the computer engineer, interjects to clarify that he is not entirely opposed to modernity, admitting to using Facebook on his smartphone. However, he concedes that with the rise of the internet and globalization, something has been lost. Even his Timberland shoes, once proudly labeled as “made in the USA,” have now experienced a decline in quality, with Troilo lamenting that even the smell was better in the past.

As the evening approaches, the paninari gathering begins to disperse, with many needing to return to their families. Before parting ways, Verdoia, who himself has a daughter named Clizia after the author of the Simon Le Bon book, reflects on their heyday. He remarks that when looking at pictures from that time, they seemed like a colorful and lively bunch, always engaged in celebration. In contrast, he notes that today’s youth spend most of their time online, expressing his hope that they may find inspiration from the paninari’s vibrant past.