“Dancers and vocalists co-star in Tanztheater Wuppertal’s vivid adaptation of the myth, accompanied by Gluck’s music.”

In Pina Bausch’s early 1975 creation, she departed from the typical discordant couples in her dance theatre to recount the tale of the devoted Orpheus, specifically warned against looking at Eurydice as he guides her from the underworld.

After nearly three decades absent from Wuppertal’s stage, this production of profound sorrow, last witnessed in the Paris Opera Ballet’s repertoire, has returned to Bausch’s hometown. This poignant rendition, set to visit the Gluck festival in Fürth, mirrors the composer’s reform operas with a balletic language that is emotionally lucid, devoid of unnecessary embellishments, and free from technical dance flourishes.

With a German libretto, Bausch stripped the opera of its cheerful overture and rejected the joyful conclusion. Rolf Borzik’s set design for the initial of four acts features the stark, brittle branches of an uprooted tree dominating the stage, while on the opposite end stands Eurydice, frozen in time in her wedding attire, observing her own funeral procession. The ensemble, clad in either black suits or chiffon, initially contort in serpentine poses, gradually merging through anguished port de bras, resembling undulating waves and introducing a motif of shielding their gazes.

Each of the three main characters—Orpheus, Eurydice, and Amor—was represented by both a dancer and a singer. This run alternates the role of Orpheus, traditionally sung by a mezzo-soprano on some nights and, during my attendance, performed by countertenor Valer Sabadus while danced by transgender artist Naomi Brito. The pair’s synchronization is exceptional, whether dancing alongside each other or apart, like when Sabadus embraces the bride before Brito commences an impassioned solo, or notably, when Brito collapses to the floor as Sabadus utters Eurydice’s name twice with profound intensity.

When Sabadus touches one of the mirrors on the set, echoes of Jean Marais’s famed poet in Orphée emerge. The film’s adaptation of Apollinaire’s verse “the bird sings with its fingers” reverberates through the dancers’ delicate hand movements.

Brito captivates as an Orpheus driven more by pain than courage, his torment heightened by Sabadus, who renders even the recitative ethereal. Moments of melancholy are momentarily relieved, notably by dancer Emily Castelli’s carefree portrayal of Amor, embodying youth (voiced by Anna Christin Sayn). A trio of apron-clad dancers, symbolizing Cerberus, the three-headed Hades hound, bring a brief smile in the second act, yet swiftly transform into menacing figures with jagged jumps, as merciless as any of Bausch’s antagonists.

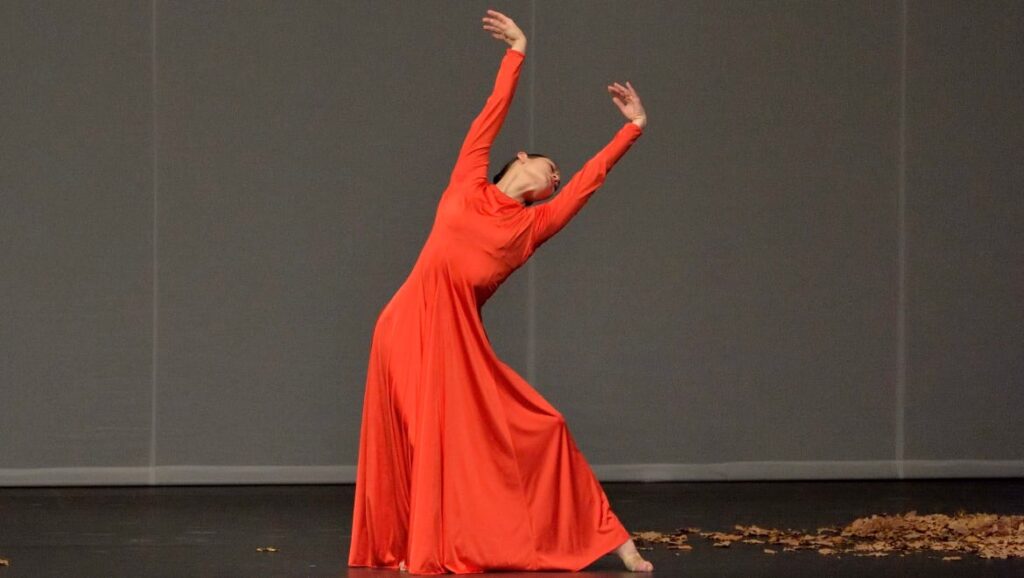

The Furies are meticulously anxious, restricting the stage’s freedom by entwining it with string. The stark difference between their dance and that of the Blessed Spirits, both beautifully played by Wuppertal’s symphony orchestra, is slightly overshadowed by a lengthy scene change between the second and third acts. However, Bausch’s luminously lit Elysian Fields offer a dreamlike elegance, with graceful backbends complementing the serene flutes. Although lacking absolute precision, the ensemble brings a delightful sense of solace, yet Bausch darkens the scene with a circle of onlookers. Soprano Naroa Intxausti shines as Eurydice, partnered with dancer Luiza Braz Batista, whose most poignant solo arrives when the singing subsides.

Under the musical direction of Michael Hofstetter and Josephine Ann Endicott’s restaging, accompanied by the haunting chorus of the Wuppertaler Bühnen from the balcony, life and love intertwine with dance. As both Eurydices are laid to rest, Brito’s graceful movement halts, encapsulating all of Orpheus’s agony in a motionless form.